ReadyMade Magazine: Majora Carter

Thursday, February 15, 2007 at 10:50PM

Thursday, February 15, 2007 at 10:50PM

February/March 2007

In the section O Eco Pioneers! Three urban development projects transforming modern environmentalism.

Raising the Roof

A South Bronx native brought sustainability to New York City's blighted borough, and revived it from the ground up.

Get this straight: Majora Carter is not anti-development. "I've embraced my inner capitalist," says the 40-year-old founder of Sustainable South Bronx, a nonprofit dedicated to improving life in the borough through green means. "I believe that sustainable, community-friendly development can also make a fortune."

Carter won a MacArthur Foundation grant in 2005 for this belief and her work, to, as she puts it, "green the ghetto." She grew up in a house that her father bought in 1948 in what was then a predominantly white, middle-class neighborhood. By the mid-1960s, however, the face of the South Bronx was changing. In 1963, Robert Moses, the city's grand poobah of urban planning, plowed the Cross-Bronx Expressway through the borough, displacing more than 600,000 residents. As a child in the '70s, Carter watched as her neighborhood became a national symbol of urban blight. Banks redlined the area, neighbors moved out, and industrial plants moved in. "I watched 50 percent of my neighborhood burn down -- blocks and blocks of structurally sound buildings were just gutted," she recalls. Soon Carter also left, to study film at Wesleyan.

As a child in the '70s, Carter watched as her neighborhood became a national symbol of urban blight. Banks redlined the area, neighbors moved out, and industrial plants moved in. "I watched 50 percent of my neighborhood burn down -- blocks and blocks of structurally sound buildings were just gutted," she recalls. Soon Carter also left, to study film at Wesleyan.

In 1997, after completing an MFA at New York University, Carter moved back home. The scene was grim. Major industries had overwhelmed the neighborhood, bringing more than 60,000 diesel truck trips through the South Bronx per week and creating one of the highest asthma populations in the entire city. "No one wanted to be here, but people couldn't afford to leave," she says.

When she heard about the city's plan to build yet another waste-transfer station in the area, she fought back and contested the proposal. Three years into the battle, she won.

After leading that charge, Carter knew she had found her cause, and in 2001 she founded Sustainable South Bronx (SSBX), a nonprofit that undertakes everything from green roof installation to "green-collar" job training in sustainable development. SSBX's seven staff members launch projects like the South Bronx Greenway, a network of bicycle and pedestrian paths along the waterfront. They also prototyped the Bronx Environmental Stewardship Training (BEST) program, a 12-week intensive begun in 2003, that offers instruction in natural resource management and prepares participants for living-wage jobs with growth potential. Of the 40 BEST graduates – most of whom never graduated from high school and receive some form of public assistance – more than 80 percent have gotten jobs in sustainable-development positions. "These are people who have both a financial and personal stake in the environment," says Carter.

Carter's goal is to connect environmental health, well-being, and economics in people's minds. "I’m pushing environmental justice for what it is – an extension of the civil rights movement. I'm not considered the best voice for the environmental movement, but I add color to this conversation in ways people don't expect."

On the grassroots side, V-Day called on dozens of local groups to participate. The result is more than 35 community events, including a self-defense class on Wednesday 15, a panel discussion with women from global conflict zones on Tuesday 13 and a domestic-violence information forum on June 17.

On the grassroots side, V-Day called on dozens of local groups to participate. The result is more than 35 community events, including a self-defense class on Wednesday 15, a panel discussion with women from global conflict zones on Tuesday 13 and a domestic-violence information forum on June 17.

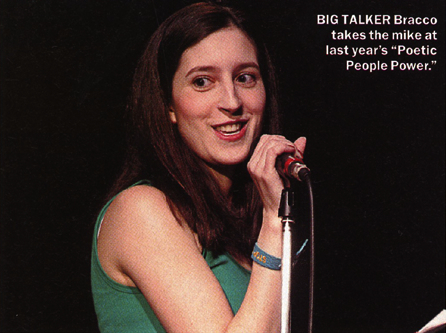

Bracco, 30, produced her first reading in 2003, in support of Poets Against the War. It went well, but she worried that the antiwar community would disperse when the war got off to a smooth start, so she decided to diversify into other causes. "Had I known how long [the war] would last, I might have kept organizing those events," she says. Instead, she used that first reading as a springboard to an annual series. Since then, while working various day jobs, she's produced two more "Poetic People Power" evenings dealing with, respectively, voting and democracy, and the environment.

Bracco, 30, produced her first reading in 2003, in support of Poets Against the War. It went well, but she worried that the antiwar community would disperse when the war got off to a smooth start, so she decided to diversify into other causes. "Had I known how long [the war] would last, I might have kept organizing those events," she says. Instead, she used that first reading as a springboard to an annual series. Since then, while working various day jobs, she's produced two more "Poetic People Power" evenings dealing with, respectively, voting and democracy, and the environment.

The 38-year-old's path to activism was a rocky one. In the '70s, Carter watched her tight-knit urban neighborhood deteriorate into a smoldering wasteland. "The whole block smelled like burning," she recalls. Industrial plants moved in, people moved out, and when she graduated from high school, Carter jumped at the chance to jet. After studying film at Wesleyan, however, she moved back home in the late '90s and soon heard about the city's proposal to build a major waste-transfer station in the South Bronx, an area already handling 40 percent of NYC's trash. It was then that she and her friends decided enough was enough, so they fought the plan—and won. "Suddenly, it was attitude city," she says of her political emergence. "No one ever asked residents what they didn't want, but no one asked them what they did want, either."

The 38-year-old's path to activism was a rocky one. In the '70s, Carter watched her tight-knit urban neighborhood deteriorate into a smoldering wasteland. "The whole block smelled like burning," she recalls. Industrial plants moved in, people moved out, and when she graduated from high school, Carter jumped at the chance to jet. After studying film at Wesleyan, however, she moved back home in the late '90s and soon heard about the city's proposal to build a major waste-transfer station in the South Bronx, an area already handling 40 percent of NYC's trash. It was then that she and her friends decided enough was enough, so they fought the plan—and won. "Suddenly, it was attitude city," she says of her political emergence. "No one ever asked residents what they didn't want, but no one asked them what they did want, either."

Using a mix of analog tools and software programs like Sonic Solutions, a mastering engineer polishes raw mixed tracks from the recording studio and enhances their flavor. "In a nutshell, mastering engineers make albums sound better," she explains. Lazar, who grew up in a musical household, first got hooked on engineering while playing in her own band after college. In 1997, after getting her master's degree at NYU, Lazar founded The Lodge, a state-of-the-art mastering house in New York City. Her current projects include Garbage's “Bleed Like Me” and Mates of State's “Like U Crazy.”

Using a mix of analog tools and software programs like Sonic Solutions, a mastering engineer polishes raw mixed tracks from the recording studio and enhances their flavor. "In a nutshell, mastering engineers make albums sound better," she explains. Lazar, who grew up in a musical household, first got hooked on engineering while playing in her own band after college. In 1997, after getting her master's degree at NYU, Lazar founded The Lodge, a state-of-the-art mastering house in New York City. Her current projects include Garbage's “Bleed Like Me” and Mates of State's “Like U Crazy.”